Welcome to the fourth edition of Drop C++, a series about the people who put the music into your favourite (and not-so-favoured) games. Over the course of discussions with a variety of musicians, composers and sound designers, this set of articles will seek to shed some light on how the music comes together, the people who make it, what inspires them and more. And with that out of the way, Volume 4 of the series is upon us.

“Movies are very linear, in terms of music, I mean,” says composer-producer-orchestrator Srikant Krishna, “And once you move from a scene to the next, you don’t hear that exact bit of music again — it might be a repetition in a different form or arrangement. But in a game, if you compose five minutes of music, it can repeat any number of times depending on the gameplay.”

Knowing how to make such repetitions work, and seamlessly transition between musical layers or themes has been one of Srikant’s key learnings over a storied career that spans cinema, television, documentaries, ad films and of course, gaming. His back catalogue is far too large to get into right now (you should check it out regardless) because we’re here to discuss only one jewel in that glittering treasure quest he calls a portfolio: The Palace on the Hill. In case you missed it when it dropped early in 2024, the game is a narrative-driven adventure that blends painting, exploration, and storytelling. Set in a vibrant, hand-painted world, players uncover the region’s rich history by piecing together stories from villagers through creative gameplay.

Running up that Hill

“It was either at IGDC, Hyderabad or at a videogame meetup in Bengaluru that I first met Mridul Kashatria and Mala Sen (co-founders of Niku Games). We met a few more times and got to know each other,” he recalls, “In 2019 or 2020, Mridul reached out to me saying, ‘Hey, we might need music, so can you just do one track?’. At this point, I’d already seen some of the artwork and a bit of basic gameplay — which was still at a native stage.” From a request for one track, Srikant ended up composing and recording between eight and 10 tracks that appear in the game.

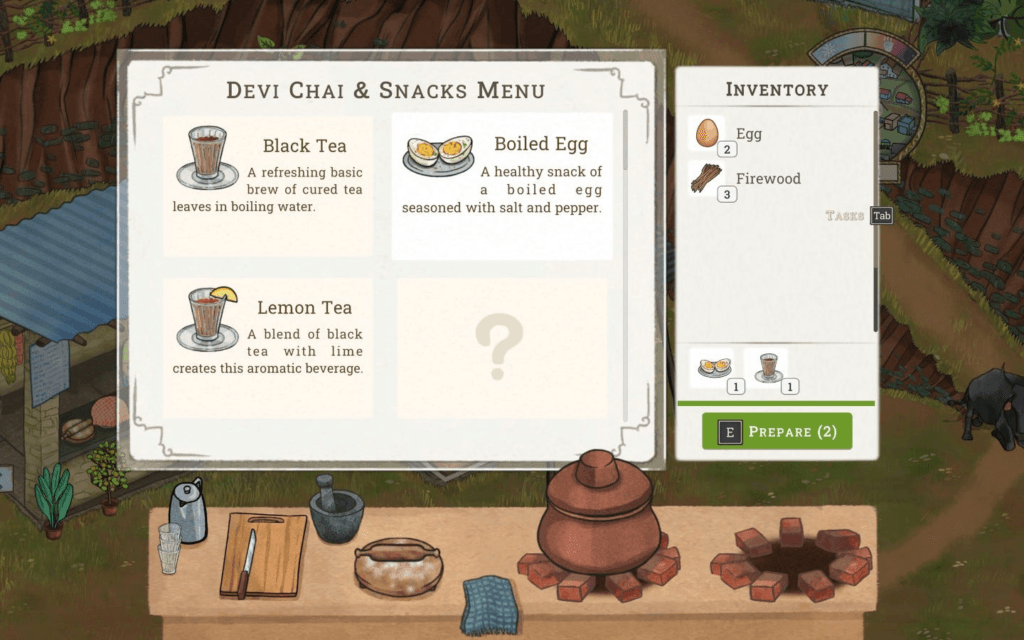

Back then, Srikant’s first impressions were formed when the game was at an extremely nascent stage. “I think they were still figuring out the world of that game, the gameplay, and the narrative. So the details that you can see at the moment were missing at that point,” he recalls, “I didn’t even have a clear idea as to whether I would be working with them at some point, because it was all so very raw. Even some of the other gameplay loops like farming, buying vegetables and fruit, selling the produce and so on were yet to be added.” At the time, he played the build for approximately five minutes, during which the protagonist Vir is exploring the town in which the game is set.

Interestingly, during the process of putting together the soundtrack, he was guided by cues rather than gameplay or even visuals. “Mridul would just tell me we need this feel, like we need music for a night scene or a boating scene or a garden-type thing. The first time I actually played the game was after it launched — and then realised just how much it had evolved in four or five years,” admits Srikant.

This brings us to the most intriguing (to me, anyway) aspects of music — the process of putting it together. When it comes to videogame music, some composers base their art on gameplay and others on the visuals. With The Palace on the Hill, Srikant relied on feel and mood. “Since I had not seen the game as such, there was nothing tangible on which to base the composition; I had some concepts and moods to work with,” he explains, “And Mridul asked me to come up with two or three minutes of music for these themes or moods.”

Armed with these pointers, Srikant got to work and set about isolating the key motifs and elements in his sonic tapestry. “The most essential element right from the beginning was the nativity and ethnicity of the Indian countryside. And to capture that, I used the flute on a couple of tracks and the main track has some flute and tabla,” he elaborates, “There’s a scene called ‘Palace‘, in which they explore the palace, and so I’ve used a bit of veena or sitar to give it a bit of a royal touch. The nighttime and boating themes are very ambient — so that you still get that feel, but it doesn’t take you away from the Indian-ness.”

One would imagine that a conceptual brief might bring with it a difference in interpretations between developer and composer, but on The Palace on the Hill, this wasn’t a case. “There wasn’t much in terms of directions to change things from Mala and Mridul, except for one track,” Srikant recalls, “I don’t remember which one it was, but I think it may have been the last track — the one that plays over the end credits. With that one, they wanted a proper change in direction; they asked for something more upbeat than the version I’d made. And that new one is what you hear now.”

On gaming

Describing himself as ‘not really a gamer if compared with other people in this industry’, Srikant concedes that in the 1990s, he played a lot of videogames with his friends. “It was one of those simple setups where you connected the joystick to the TV and could play games like Contra, Dangerous Dave and a bunch of racing and shooting games,” he says, “Later on, I was addicted to two games, FIFA and Age of Empires. As a teenager, it was the former that really drew me in, and I learned a lot of the rules of football (like offside) and the names of footballers through those games. Age of Empires really intrigued me, both musically and in terms of gameplay.”

In recent times, such titles as Rollercoaster Tycoon and Limbo have grabbed his fancy, but the love affair with Age of Empires burned strong. It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to say that this informed his choices when Srikant embarked on a Master’s programme at the Berklee College of Music, Valencia. “The course was called Scoring for Films, TV and Video Games. And in one of my semesters, they explained games like Age of Empires, where you have different modes. At first, you’re just exploring the map,” he says, “Then you start building your community, your buildings and all that. And then when an enemy attacks you, there’s another kind of music. So it’s like one bit of music fades out and another fades in seamlessly.”

This wasn’t something he realised while playing the game, but the experience stayed with him and, in time, helped him understand how music works and how to implement sound in FMOD. “We also did a bit of sound design, in terms of taking one game as an assignment, creating a sound design for it and maybe recording voiceovers. And all of this was very insightful in terms of learning about how videogame music and sound work,” Srikant adds.

Another aspect of videogame music that fascinates him is how a number of AAA studios use massive orchestras to record epic scores. Naming Penka Kouneva and Hans Zimmer among his biggest inspirations, he notes, “The music in some AAA games transports you to a high-production Hollywood world. It’s very epic and extremely inspiring… and it always has this grand scale. Almost like watching a super superhero kind of a film.” That isn’t to say that Srikant isn’t au fait with non-AAA composers — he includes Stephen Mellon and Joe Hisaishi among his other favourites.

Behind the music

Stepping away from videogame music, Srikant has the rare distinction of having worked with one of his personal heroes. “One of my biggest inspirations is definitely AR Rahman, and I’ve been lucky to work with him on a number of films as well — mostly in Tamil,” he says, listing, “There was a film called Ponniyin Selvan: I, a couple of Hindi movies including Maidaan, and a Malayalam film called Aadujeevitham. The latter is a survival story about one person through the ages, through time, nature, and all sorts of difficulties, and just waiting.”

John Williams, Danny Elfman, James Horner and John Powell round off his list of biggest inspirations when it comes to writing music for film. Particularly, the last one on that list. “Powell does a lot of animation films like How to Train Your Dragon and these have very inspiring soundtracks that can actually be used in games to great effect,” says Srikant, “I think I remember playing some racing game with a playlist full of high-energy tracks on VLC or Winamp in the background. So in a way, music has directly influenced my interest in gaming as well.”

And this brings us to the all-important artistic process. “Sometimes an instrument can trigger the ideas. A certain instrument or an idea from the creator can often give me some direction or inspiration. Sometimes when I’m lost, I listen to a few soundtracks that are in that particular mood,” Srikant explains. A recent example of this was when he was working on a short film that was a comedy-thriller. A decision was taken to seek out a sonic space that was akin to something like The Grand Budapest Hotel — slightly comical, but also mysterious. And listening to soundtracks of films, including the Wes Anderson one, helped him find the direction to compose the score.

“Sometimes the stimulus can be external, in the form of music that already exists. So as and when I listen to music from a film, show or a soundtrack, I put it on a Spotify playlist — there are different playlists for different moods,” he explains, “And when I’m running short on inspiration, I jump into those to see what gives me some kind of direction or idea. Often, even listening to 10 or 15 seconds helps because it’s enough to trigger an idea.”

And in terms of turning ideas into music, Srikant has one firm ally. “The keyboard. That’s the only instrument I know — it’s what I used to play in my college band too,” he says, “I have a digital piano at home. And that’s where I sit and jam ideas to see what works. If I like something, even if it’s a 30-second stub, I’ll grab my phone and immediately record it, and then label it according to what mood I think it suits. This is one way in which I can keep building a bank of ideas.”

Finally, what’s next for the man who gave a sonic identity to The Palace on the Hill? “A couple of games are still in talks, they want me to do either just music or both music and sound design. So we’re just in the initial stages of talking,” he divulges, “In the meantime, I’m always doing orchestral work, like doing arrangements for some film songs. Apart from that, I have composed five soundtracks that are quite epic in scale and I want to release that as an album, like an epic soundtrack album.”

The aim of this endeavour, he adds, is so people listen to it and are able to come to him with a request for a particular type of music. “Instead of coming to me and then listening to my music, I feel this would make for a more productive conversation between us,” Srikant says, “If they already know what my music sounds like, they won’t ask me to do things that aren’t really in my wheelhouse.” We’ll keep an eye out for that album, and meanwhile, if you haven’t already, do check out The Palace on the Hill.