Welcome to the seventh edition of Drop C++, a series about the people who put the music into your favourite (and not-so-favoured) games. Over the course of discussions with a variety of musicians, composers and sound designers, this set of articles will seek to shed some light on how the music comes together, the people who make it, what inspires them and more. And with that out of the way, sit back, relax and enjoy Volume 7 of the series.

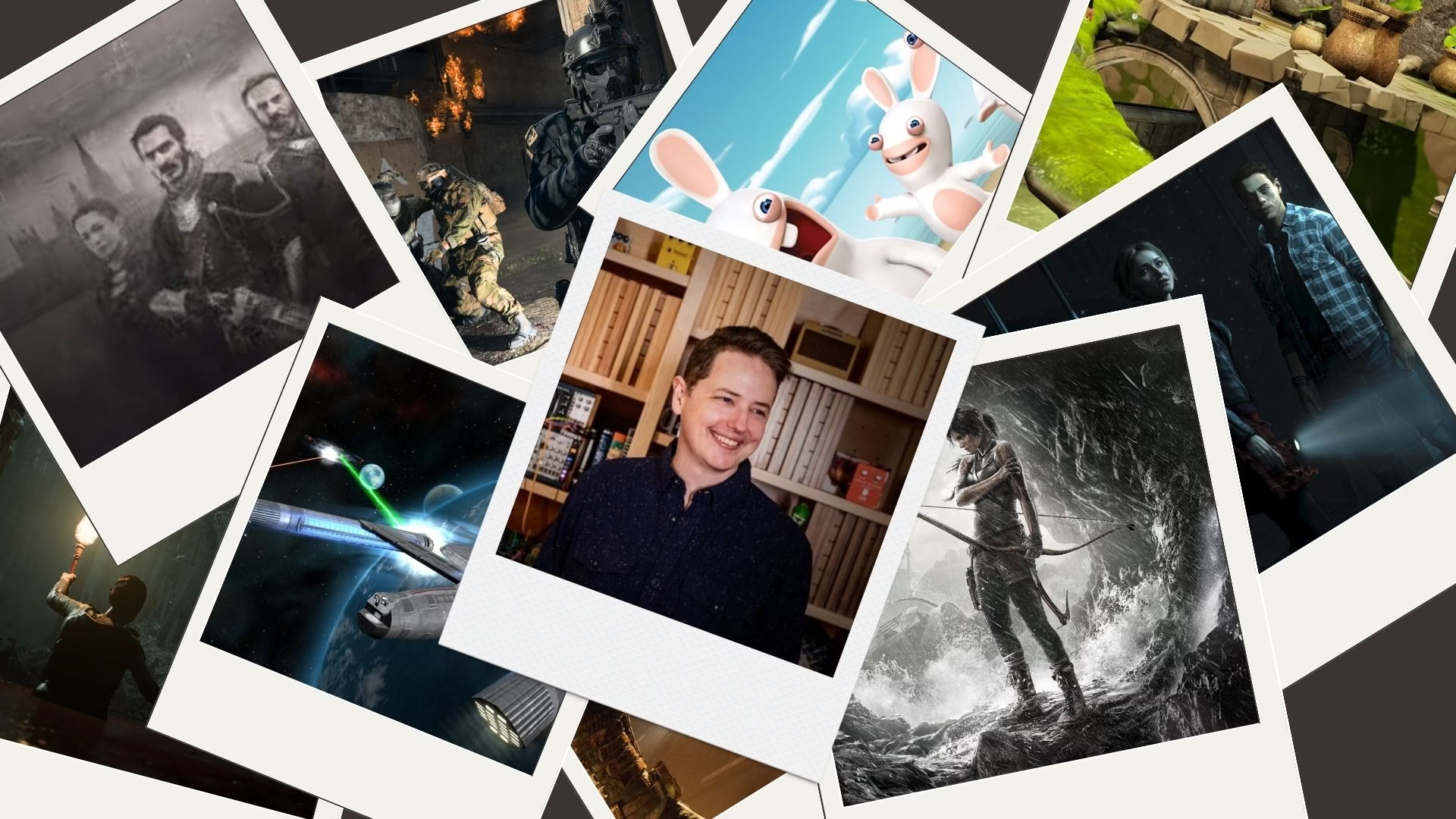

At a little after 4 pm in North Carolina, a tiny bird (possibly a budgie, perhaps some sort of parakeet; I’m no ornithologist) pops up on the mixing console in Jason Graves’ studio, and proceeds to hop onto his person — and in so doing, sets the tone for what turns out to be an intriguing, frequently amusing and sometimes surprising discussion. (Update: Said bird was later confirmed to be a Pineapple Green Cheek Conure) The music composer for such games as Dead Space, Until Dawn, Tomb Raider, F.E.A.R. 3, Alpha Protocol and numerous others recently completed work on Siren’s Rest, a story expansion for last year’s Still Wakes the Deep (read an interview with lead designer Rob McLachlan here) — for which he’s been nominated for the World Soundtrack Awards Game Music Award 2025. Let’s dive right in.

Set on an offshore rig, Still Wakes the Deep is a Lovecraftian narrative adventure packed with elements of horror. The expansion takes place in a different timeline (10 years after the events of the base game) and features different characters. “The location is more or less the same, but it was different enough overall that even when the team at [developer] Chinese Room explained it to me, I was thinking, ‘This sounds so different, I don’t think we need to use most of the same sounds’,” says Graves over a video call, “Daan [Hendriks], the audio director agreed and said they wanted to use new sounds, instruments and textures to separate this from the original game.”

Describing Siren’s Rest as something that stands on its own, he notes that it is an ‘extension of the sonic universe’ as much as the story universe. That is to say that just as there are related characters, there are related musical themes. Related, but different. A key part of this differentiation is that the context has undergone a major change. “[Unlike the base game], in Siren’s Rest, you are underwater the whole time — you’re in a deep pressure suit. And realistically, in one of those, you only hear sounds of things you are touching,” he explains, “So if something big goes by or there’s a loud sound in the water, you might hear that, but it’ll be very muffled. Most of what you’re hearing is essentially your breathing because you’re inside this giant dome and the music had to be able to represent itself accurately while staying faithful to the rather claustrophobic, tight and muffled experience that lasts the entirety of Siren’s Rest.”

Narrative adventures

Having lent his music to a variety of such narrative-led and story-driven titles as The Dark Pictures Anthology series, the forthcoming Directive 8020 and the aforementioned Until Dawn and Still Wakes the Deep, I’m curious as to what it is about this type of game that attracts Graves. “I do enjoy them,” he says matter-of-factly, “I come from the world of scoring film and television, which is obviously very story-driven and very narrative-driven, and the kind of games that I like to play are very much the same.”

Pointing out that while he does work on titles like Call of Duty, which do have campaigns and plots, but are more of a multiplayer experience that warrants a different kind of score, what he truly loves is character development and forward momentum in terms of plot and story. “The real fun ones from a musical arc standpoint are the genuinely narrative-driven games where there’s not a multiplayer mode,” Graves notes, “It’s all focused on this one character and their unique perspective, whether it’s something like Tomb Raider or Moss — both different kinds of games, but still very narratively-driven — or Still Wakes the Deep, a horror game or a fantasy game. I think I always lean into that character arc because I want to have that same feeling when you finish the game that you would feel when you finish watching a film.”

Context is king

Dabbling in a variety of games and game types means there obviously can’t be a singular ‘one size fits all’ approach to music design. And context has a major part to play in all of this. “A lot of times, [the approach to music] will depend on how much action is going on in the game and the background,” he offers, “So if the action is exploration or puzzle-solving, it would denote one kind of music and if it’s actual action with a lot of explosions or gunfire, that would ask for a different music.”

To better illustrate the point about sculpting music, Graves draws on Moss/Moss: Book II and Siren’s Rest for comparison because, as he puts it, they are ‘very, very different, although very similar’. As mentioned earlier, the Siren’s Deep experience is a tight, muffled and claustrophobic one. “[In contrast], when you’re exploring in the Moss games, you’re either in a big abandoned castle or a forest, and there are lots of very ambient, far away sounds. There are birds, there are leaves rustling in trees, and it’s all very natural,” he says, “So I had a lot more space with the music to be a little more orchestral and a little more lush, unlike the custom-recorded sounds in Siren’s Rest that were processed to have this sort of pressure and a feeling of being trapped underwater.”

The composer goes on to add that if you were to take the music from the Still Wakes the Deep expansion and drop it into Call of Duty, you probably wouldn’t hear it at all because it would be completely obliterated. When competing with gunfire and explosions, you usually need a lot of big percussion and things of the sort to cut through the mix. Similarly, the music from Call of Duty was dropped into Moss, it would sound, by Graves’ own admission, overwhelming and ‘foreboding, in a bad way’. “You want the music to feel like it’s part of the sound design. And I don’t want to say you don’t want to notice the music, but you don’t want to call too much attention to it, unless it’s something that you are doing on purpose for a certain moment. And then you retreat into the background,” he says.

Rebirth of the Tomb Raider

The 2013 reboot of the Tomb Raider franchise set about redefining what players knew about the household name character Lara Croft. And with several awards and nominations under its belt, the music for the game went a long way in aiding this process. “Crystal Dynamics was very clear from the beginning that they wanted new music; they didn’t want to quote the original theme or have any sort of homage or responsibility to use it anywhere,” he recalls, “They wanted something really new and original and they wanted to be able to take that theme and use it from then onwards. I was brought on board to create a thematic template and to score the game.”

With this brief, the first thing Graves set out to do was put together the theme music and work on it. “Usually I sketch things out on piano. Obviously, I wouldn’t be sketching out the score to something like Siren’s Rest on piano because it’s very textural and ambient,” he says, “But normally, if it’s a theme, I feel like you should be able to hum it. And if you can hum it, you can play it on the piano. So I did a very simple piano sketch and sent it over to them as a test.” As it turns out, this was the version that was used, except for one little change: A chord was switched out. And the rest of it is what we can all hear on the soundtrack of the game.

“Other than saying we want a new theme, they gave me a lot of leeway and I was concerned that maybe they were going to want big taiko drums and super action-adventure stuff, like lots of French horns from the very opening of the game,” Graves discloses, “As I already admitted, I love character arcs. So for me, she’s starting out as a new Lara Croft, and she hasn’t experienced all the confidence-building adventures and everything that we’ve known from the previous games. This is her young, not confident, inexperienced and unsure of herself, so my pitch was let’s do solo cello or maybe solo piano at the beginning and not have anything that thematic.

“Lean more towards textures at the beginning, and as we progress through the game, and she is earning her stripes and learning the ropes, we build the theme. And then in the last act of the game, once you climb up to this new level, we pull out the big drums and the more heroic orchestra, but by then you’ve heard little pieces of this theme in a solo cello or a piano or something that’s really quiet,” he continues, “Now you get the big powerful version and you feel like you’ve earned it. The first time it really comes in, I had so many people tell me that those were some of their favourite parts of the game and they felt really empowered. That Crystal Dynamics allowed the music to hold back for that long gave it a really big payoff and of course, the closing cinematic and everything are really nice and big. But I love that they didn’t try to shove it down your throat in the beginning.”

Reframing Warframe

Digital Extremes’ online multiplayer third-person shooter Warframe launched back in March 2013. It was seven years after the game had been launched and racked up millions of players that Graves was brought on board to make music for new sections of the game. Creating music for new titles is one thing, doing that for sequels is another, but how does one write music for a game that’s already out in the wild? “That was a 50-50 tightrope walk because I wasn’t as familiar with the style of Warframe, but the audio director definitely was because he’d written a decent amount of the music. And the composer that I was coming on to tangentially write music next to was Keith Power, who I believe is still writing on Warframe,” he says. “I’d worked with Keith for a couple of years on Magnum PI and Hawaii Five-O and things like that, so we both had a very similar style that lent itself to Warframe automatically.”

It was here that audio director George Spanos was extremely helpful in terms of keeping things simple. “He said really simple things like, ‘We use Gregorian Choirs a lot to note this one thing in the game, and we’ll use electronic percussion to resemble this other thing in the game’ and ‘We also use orchestra, but a lot of times we make sure that it’s doubled with synths because that represents the ambiguity of synthetic versus organic’,” Graves recalls, “And it was a set of very general statements like that, because I don’t think anyone wanted me to feel obligated to do things a certain way. There were some guardrails, but I could still play around as much as I wanted within those. I ended up writing for a year or two with them, and it was a lot of fun because it was this super-hybrid mashup of stuff that I hadn’t been able to try before.”

The Dead Space saga

One of Graves’ finest bodies of work, in my opinion anyway, is the music he composed for the Dead Space series. The games, particularly the first two, were frightening to start with, but the music served to push them further into the stratosphere of scariness. And between 2008 and 2013, he’s been involved in every single iteration of the franchise. “From the first Dead Space to Dead Space 3, a lot of it had more to do with the audio directors than anything else. Now, of course, the audio directors were taking commands from on high, from creative directors and producers and things like that. But with the first two, we were really given a lot of freedom,” he smiles.

Graves reminisces about the original game in the series and how no one outside the core team knew what they were doing or that they were even making a game of this sort. “We were given complete freedom to do whatever we wanted and my only real instruction was to write the scariest music ever written in the world,” he says with a laugh, “And we did the first game and it was quite popular. So for the second game, EA asked us to do more of what we were doing the first time around.”

It was around the time that he was working on Dead Space 2 that he reached out to Garry Schyman (music composer for such series as Bioshock, Destroy All Humans and Middle-Earth) for advice. “I called him because he had just finished Bioshock 2. I told him that I didn’t know what to do for Dead Space 2. I mean the first one won a BAFTA and all these other awards, so how am I supposed to better that?” he recollects, “He said to me, ‘You’re not beating it or making it any better. You just need to do kind of the same thing but different’. It needed to feel like it was in the same universe, but be different than what I did before. And I realised that I could make the orchestra sound bigger and louder if I contrasted it with something that was really quiet and intimate. Which is why we ended up using a string quartet for Dead Space 2, so I could do these really quiet and intimate string quartet solo sounds and then hit you with this giant orchestra. If you think about it now, it makes perfect sense, but at the time, it seemed crazy.”

Noting that they were left to their own devices with Dead Space 2 and allowed to make even more scary music, the series had begun to gain traction. “The decision was made to market Dead Space more as a multiplayer shooter because that’s what was making a lot of money at the time. With the third game, we went through three audio directors, and I think it was because people were really burnt out on working on such scary games,” he says, “There was no audio director for a while and the creative direction of the game really had no true guardrails. It’s like [the powers-that-be] kept rewriting the map. ‘We want it to be more action’. ‘We want it to be a little less scary’. ‘It needs to have teamwork’. And I’m thinking that doesn’t sound scary to me.”

According to Graves (and there won’t be too many people disagreeing), the reason people liked the first two games was because they gave some really interesting and unique scares. But that was all changing. “The direction became more commercial, which often happens with franchises like these, and ‘how many game units are we going to sell?’ becomes a priority over ‘how creatively freeing is this project for the developers?’,” he says with an almost self-deprecating laugh, “It takes a pretty unique developer or an even more trusting publisher to leave the reins alone.”

Journeying into established universes

It’s one thing to climb onboard a games franchise in its second or third outing, but what happens when you’re creating music for a franchise that has existed for years in film and/or television? Star Trek, Transformers and The Lord of the Rings are just a few of the established universes into which Graves has forayed. I venture to find out just how limiting it is to work in universes that have musical themes and motifs set in stone. But the response I receive is quite surprising. “I think almost unanimously, all of those projects were dangerously liberating because the video game publishers could not afford the rights to the official music in the games,” he says, “I loved working on those games, but it puts you in a really weird place because you can’t use Jerry Goldsmith or James Horner’s music for Star Trek, let’s say. But the game developer and publisher want to hear a theme that evokes the same feelings as Goldsmith or Horner’s themes.”

Graves proceeds to vocalise the immortal and iconic Star Trek theme, and the dilemma is instantly clear: Just how do you make Goldsmith’s theme without making Goldsmith’s theme? “This score is one I’ve listened to all my life. So part of the process is trying to embody the emotions that those themes evoke in me — kind of like regurgitating them through my lens and how I hope that it might make people unfamiliar with the original film feel,” he says, “So I comforted myself by thinking maybe some of the people that are going to play Star Trek: Legacy and hear my music will not be comparing it to Goldsmith or Horner because those movies are fairly old in the zeitgeist of human culture. And so that gave me a little more freedom to not feel completely crushed creatively the whole time. It’s hard enough to write music with your own demons and issues, and just work something out that you think sounds good, let alone comparing it to any of these titans of industry in the film music world.”

Graves moves on to another franchise and points out that while working on The Hobbit in 2003, only The Lord of the Rings films were rumoured to be in production. There didn’t seem to be any Hobbit film on the horizon, and the shadow of Peter Jackson was nowhere near as omnipresent on the landscape as it is today. “Even so, I love the book, so while there was freedom, there was also a great deal of personal responsibility I felt. It’s the same thing with any of those movie-based tie-in games or any of the ones that are based on Transformers or just some general Marvel things. It’s a double-edged sword: Super exciting, but you just really don’t want to mess it up,” he adds.

OG titles or sequels?

Over the course of a remarkable career, Graves has worked on numerous original titles and a whole host of sequels. But does he have a preference between starting afresh and picking up on an existing franchise? “They’re equally challenging for different reasons. If we look at something like Moss, the original game had a thematic encyclopedia that I had built so when the second one came around, there were themes that I could use. I knew there were some new themes that I wanted to write, but because of the nature of the game I didn’t feel a need to be super-different from the first one,” he says, “But if you look at the original Dead Space and then the second one, I felt more pressure to do something different, and also EA wanted the score to be bigger, which was a little challenging because I already had the entire orchestra doing all this crazy, ‘as big as it could get’ stuff.”

Reasoning that at the end of the day, when it’s all composed, recorded and mastered, it is still the game that drives the music. “So it’s not necessarily easier or harder if I’m doing a sequel to something that I’ve scored before, or if I’m doing it something that someone else has scored before,” Graves says, “That said, I don’t think I’ve been asked to use other themes. Usually I’m doing my own themes, or if I’m using other themes, they’re themes that I wrote for something. They’re basically all seemingly impossible when I first start.

It seems like there’s no good ideas, and then you fast forward through a lot of blood, sweat and tears and you look back when it’s finished and it’s like, ‘Oh, of course we used a string quartet in Dead Space 2 and contrasted it with the giant orchestra.”

The all-important process

Over the course of the Drop C++ series so far, we’ve encountered musicians with very different approaches. Some prefer to play the game before putting down a single note, others opt to watch gameplay videos to get a sense of what the game will be like, and others find it’s best to work with a description of the mood and take it from there. For Graves, it’s a mix of all three. “Normally, the general idea is: Send me everything you possibly can about the game and that would be scripts, concept art, Steam codes so I can play through the game etc,” he says, “But, a lot of times it’s better to just watch gameplay footage because the game will be broken inevitably at different places. I’ll end up spending two hours trying to get to the point that the audio director and I were discussing, and I’ll text them and they’ll say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s broken today’.”

Adding that it’s a lot quicker for him to just have a 20-or-so-minute gameplay capture and be able to reference it throughout, he does like the ability to play the game once the music’s being implemented. “The idea is to just immerse myself in this world that the developer has probably spent at least the last year or two building. If I’m playing and just walking around in the game, I’ll turn on ‘God Mode’ — particularly if it’s a shooter game — and just explore and walk around and immerse myself as much as I can,” reveals Graves, “If I start working on some music, maybe I’ll play the music in the background and turn it down a little bit to get a balance. I have a 70-inch TV where I play the picture, so it feels more like a cinematic experience with the lights turned down. And then from there, it’s just a matter of discussing basically what works and what doesn’t. And treating it a little bit like a film.”

“So here’s this 20 minutes of gameplay and here are the story beats. Here’s where you could make a different decision. And then we talk about the music, and I’ll end up sending things in. They put it in the game and we play it and then there’s another discussion,” Graves says, “We’ll go, ‘Well, that that worked really well’ or ‘That really didn’t play how I thought it was going to play’. Things get tweaked, another level comes on, and we move forward; then we go back and look at the previous level. That’s really why game development takes a long time because everything’s happening in real time. Always moving.”

The story so far and beyond

Looking back on an already storied career, Graves pinpoints Moss: Book II as his favourite soundtrack to work on. This, he mentions, is because the music was very lush and melodic, the story was very well done and at the end of the day, the experience left him feeling relaxed and as though he’d been ‘having a massage all day’. “As opposed to doing something like a super tense shooter or a scary game that leaves me tense or scared at the end of the day, but it’s sort of like, ‘Whew, okay, that was really cool’, but it’s also more taxing.” As for soundtracks by other folks, he points to Joris de Man and The Flight’s work on Horizon Zero Dawn and Horizon Forbidden West as his favourite in recent times.

And finally, with such a heaving resumé, portfolio and IMDb page, the composer is in a position where he can pick and choose his assignments. But what are his key considerations before signing up for a project? “First of all, there needs to be like a good vibe with the audio director. Now, most of the time, if someone contacts me about something, my criteria or boxes are getting ticked pretty easily because game people tend to be a lot more collaborative,” he says, “So we’ll even have an initial conversation, and they’re just as curious about my behind-the-scenes experience as I am about their game, and a lot of times that symbiosis really turns into something very interesting.”

The conversation will continue, he goes on, with certain points from Graves’ back catalogue being referenced. “They’ll ask about ‘When this happened in a particular game, the music did this, how did you do that?’ or ‘What was the instrument you used for some other particular thing?’ or just technical questions,” he explains, “Because the interesting thing about working in games is that the composer might have three to six or seven different game projects at different stages happening all at once. I’m a freelancer, a work-for-hire and I’m not on a salary, but the audio director is. And they’ve been doing nothing but this game for the past two years, so they tend to have blinders on. Coming in as an outside source can offer a fresh perspective or a breath of fresh air, and I embrace that.”

Next, there’s the whole ‘personality thing and the vibe’, as he puts it. The creative industry, as is well-known, is built on people-to-people connections and the absence of those can doom any project. “And then of course, is the question of whether this is the kind of game I could get behind and be excited about? And are we talking about interesting, transitory brand-new textures or interesting ideas for the music where it’s not just going to be wallpaper in the background. I like it to mean something. And not necessarily have it playing all the time,” he says, “I think of music in games the way you would think of music in a film, unless it’s Star Wars or something that just really needs to have that playing all the time. If all of these factors tally, then I know that we’re moving in the right direction.”