This month, eight years ago, Xbox Game Pass was announced. The service launched later that year as an online library of around 100 games that players could download and play, so long as they remained subscribed to Game Pass. The following year, Microsoft stated that first-party titles would arrive on the service on launch day. Flash-forward four years, and Call of Duty fans rejoiced as the Redmond tech giant made known in January 2022 its plans to put the soon-to-be-acquired Activision Blizzard’s games on Game Pass as well.

Let’s move even further forward in time, and 2025 is set to be Microsoft’s biggest year in gaming for a while, with a number of eagerly anticipated first-party titles arriving on Day One on the subscription service. In the wake of the Playstation 5 Pro launch, you’d imagine this would be a great time for Team Green to play up the merits of their own console, but no. Something else was cooking. This:

To summarise, in case you didn’t wish to put yourself through the ad, Microsoft is continuing to double down on its role as service/software provider, and underplaying its hardware-manufacturing department. To be clear, this shift away from hardware (despite launching at least one new controller every month or two) is neither a new thing for Xbox, nor unprecedented for Microsoft. After all, there’s been the Zune, the Kin, the SideWinder peripherals, the SPOT and Timex Datalink smartwatches and most egregiously, the Windows Phone. To see Xbox join that illustrious list would be heartbreaking, but not entirely unexpected. Let’s take a quick look at some numbers.

While in the press release issued at the end of last month, Microsoft indicated that its “Windows OEM and Devices revenue increased 4%”, it was revealed in its financial results that Xbox hardware sales are down 29%. Further, CFO Amy Hood observed on the earnings call that that Xbox hardware revenue “will decline year over year”. Meanwhile, Xbox content and services revenue increased by a reported 2% on the back of strong showings as a result of the increase in PC subscribers for Game Pass, and the launches of Call of Duty Black Ops 6 and Indiana Jones and the Great Circle.

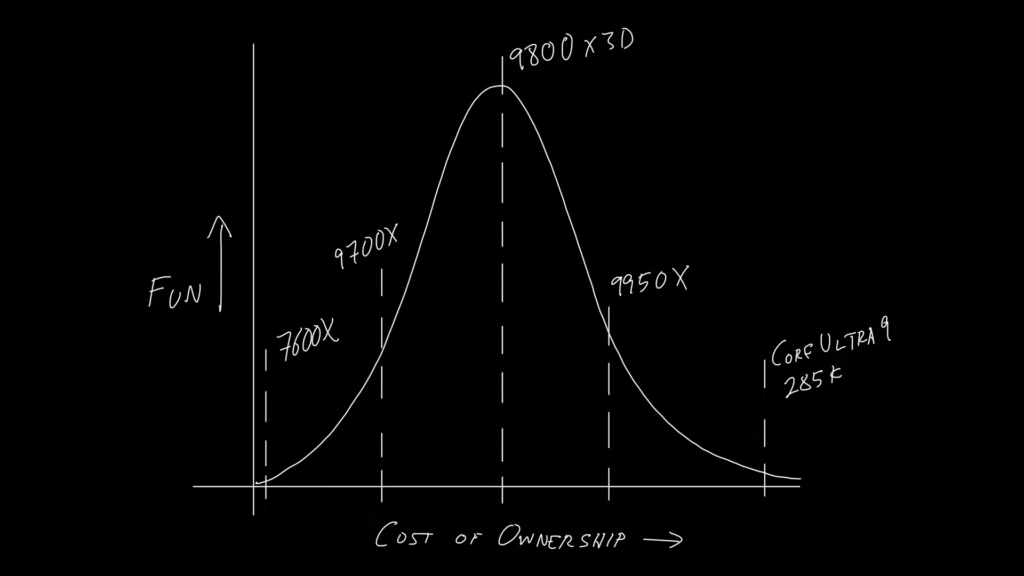

Before going any further, it’s time to address a few realities. Let’s start with the fact that the Xbox has traditionally always lagged behind the Sony PlayStation. It was only in the seventh generation of consoles that the Xbox 360 put up a spirited battle against the widely-panned PlayStation 3, and fell just a few million short in sales. The gulf during all other generations has been vast. This could be down to a lack of exclusives, little appetite to grow the user base (particularly in emerging markets), the fact that Xbox seemingly stopped innovating after 2010’s Kinect, or the (more-recent) availability of Xbox games on other devices. What is clear though is that Xbox hardware is no longer a priority and that Microsoft has been increasingly moving in a software-first, evident in its revenue increase in ‘content and services’. What is less clear is why its own first-party game studios appear to be being sacrificed at the altar of Game Pass.

As mentioned above, the decision for first-party games to arrive on the service at launch was taken many years ago. This remains one of the biggest draws of picking up a subscription, since it works out far cheaper for the customer to check out the latest releases. Sure, you don’t actually own the game, but viewed as a library card, Game Pass can be quite an affordable way to sample new games, and complete them if you so desire.

Certainly, some studios make a bit of money from their game being downloaded through Game Pass, but they tend to make a lot more when customers actually buy the game. It’s obvious, but it needs spelling out. And the argument can be made that this is all well and good for a tiny number of AAA titles that will be downloaded over a million times, but what of the rest of the games on the service? For a very small fraction of those, it’s the increase in discoverability more than the financial gain that drives the decision to be on Game Pass. As for the rest, well, they tend to take a hit. A rather sizeable one.

Back to people getting hold of games, and there’s usually two ways of doing that: In a physical or digital form. It was widely reported during Microsoft’s mass layoffs last year that the team bringing physical media to retailers had also been axed. And in the months since, we’ve seen reports of physical copies of Starfield being pulled from shelves, the launch of an all-digital Xbox Series X console and the fact that while titles like the upcoming Avowed are not being sold on disc, other recent drops like Indiana Jones and the Great Circle require a hefty download even with the disc in your drive. Probably the cruellest of all is that a number of the ‘physical’ editions of games these days come with SteelBook cases, but nothing to actually put in them.

So if you’re not a stickler for something tangible to hold, there’s always the digital option. The obvious disadvantage with this method is that you can’t lend the game to a friend, hock it on the second-hand market, or actually own it (because a few lines of code in the form of an update can brick the game when a studio decides it doesn’t want you to play it anymore). However, it is arguably a more immediate way to get your hands on a game — a decent internet connection means you can be playing a game within minutes of purchase (recent events notwithstanding).

The issue with this method, particularly in markets like India, arises when publishers decide not to practice regional pricing. This is seen most clearly in first-party Xbox releases. When games retailed in the US for $60, the price in India was around Rs 4,000 or thereabouts. Now, the jump to $70 has seen the price of base editions of first-party Xbox games hit Rs 6,499 (never mind the price tag of almost Rs 9,000 you’ll have to cough up for some skins, a digital art book and five days early access that masquerades as a special edition).

From the outside, it seems strange that Microsoft is going through the effort of acquiring studios, only to stiff them when the time comes to letting them make money. A case in point is Tango Gameworks that was hung out to dry after making the successful Hi-Fi Rush (Note: The studio has subsequently been given a new lease of life by Krafton). Cynically, it could be argued that ‘pumping out games, shutting studios, acquiring new ones, rinse and repeat’ is all about boosting the bottom line, keeping investors happy and all the rest. But what of everyone else?

Ultimately, the presence of diverse games on Game Pass is obviously great for the service, but how sustainable is this for the people making those games? And what is going to be the eventual impact of this particular model of game publishing on the industry at large? The jury’s still out.